Short story for NTT 11/14/24

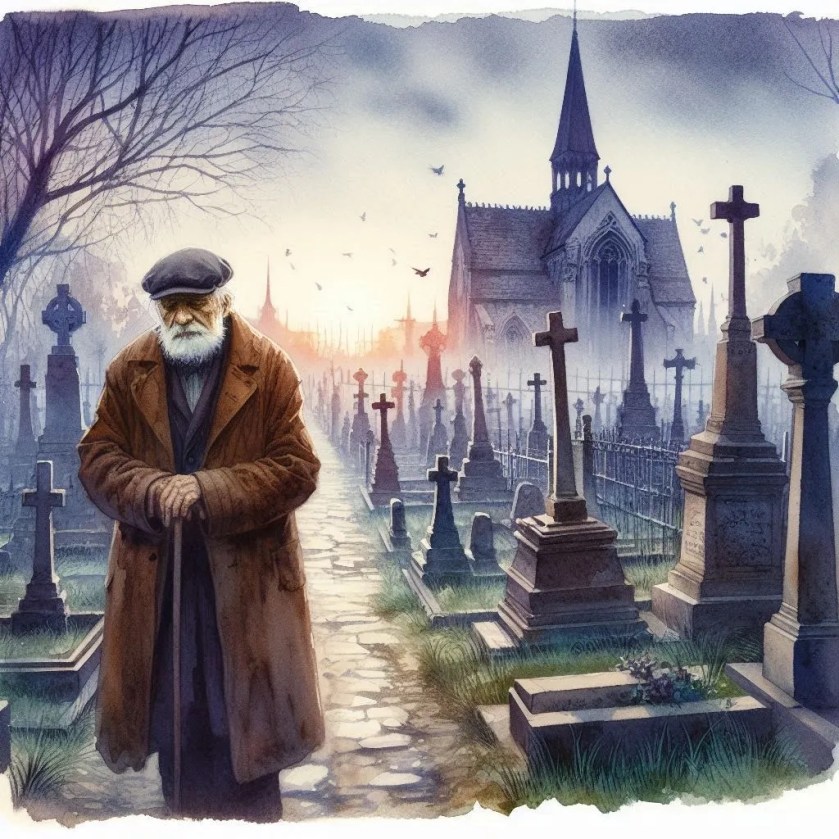

This short story is for Kevin’s No Theme Thursday for 11/14/24. Every week, Kevin produces amazing artwork that serve as inspiration for prose or poetry. Check it out!

The chilly January wind swirled around me, but I barely felt it, lost in thought; had half a century really passed? I painfully knelt and traced my gloved hand over the letters, newly hewn into the polished granite.

The letters on the stone to the right were already beginning to fade after fifty summers and winters. I traced these as well and bits of rock crumbled at my touch.

As I stood to take my leave of the church yard, it was only my respect for the hallowed ground upon which I stood that prevented me from spitting in contempt on the icy soil where one of them lay.

My earliest memory was also in winter, a Christmas Day when I was four or five. We attended services at our village church, and after dinner, my family—Father, Mother, Prudence and I—opened gifts in the living room.

I recall just bits and pieces. The piney smell of the tree, decorated with popcorn and ribbons. The cold polished wood floors. A warm fire in the hearth. And Prudence’s scowling, sullen countenance. I had received a small wooden train set, while she had gotten a prized doll; and even at my early age, it was easy to recognize the brooding envy with which she regarded me and my gift.

Older than me by eight years, my sister would certainly never be described as attractive. Her disposition matched her appearance, harsh and cruel, prone to intemperate outbursts and cutting remarks. On this particular morning, she waited for her chance. As soon as Father and Mother had left the room, she grabbed two of the train cars and bashed them repeatedly against the floor until the wheels broke off. Then she placed them back in front of me and picked up her doll.

I cried but she blamed it on me; so not only was my present ruined, I was paddled and sent to bed with no dessert. Thus began my life with Prudence.

As I grew, it was became obvious that Prudence was the favorite. Father and Mother were solicitous of her moods and spared no effort or expense to please her. Father was a lawyer, and apparently money was not a concern judging by the attention and luxuries they lavished upon her. Not that they improved her sour temperament; but they helped me understand quite clearly our differing ranks.

I’m certain that my decision not to study the law and take over Father’s practice lowered my ranking even further; and when I became the village Postmaster—a respectful position, to be certain, but not nearly as prestigious as a solicitor—the derision I endured was wearying. But I enjoyed my job, being out and about in the village, and I think my contentment made Prudence even more envious.

The years passed without much excitement. Of course, interesting things were going on in the world; railroads were being built; the American West was expanding; and in England, Queen Victoria ascended the throne. But nothing extraordinary happened in our little corner of New Hampshire.

By 1832, I was 30 years old, and Prudence was 38. It appeared that neither of us were destined to be married and blessed with families of our own, even though it’s something we both very much desired. Our reasons differed: For me, there were simply no eligible women in Hartford Falls; and in Prudence’s case, her foul temper and angular, spindly appearance kept would-be suitors at a careful distance.

One evening, Father excused himself early and went upstairs to bed, mentioning a headache that had been plaguing him for several days. An hour or two later, the rest of us retired to our bedrooms, the oil lanterns making long shadows as we climbed the stairs.

A scream from Mother’s room sent Prudence and I running.

“Oh my God,” she cried. She clutched one hand to her bosom and with the other, pointed at Father who lay in his bed with his eyes staring sightlessly.

“I think he’s passed!” she cried. “I think your father is gone.”

Prudence held her as she sobbed. She stopped long enough to address me.

“Greyson!” she snapped. “Go get Doctor Wilson. Hurry!”

I had felt for a pulse and found none, nor had I seen any fog on the mirror I held to his mouth, but I went anyway.

There was nothing to be done, and a few days later, most of the people of the village stood by respectfully as Mother cried, the Pastor read the twenty-third Psalm, and Samuel Becket, Esq, was laid to rest on a June afternoon in 1833.

Father’s estate provided for us well; his law practice was even more lucrative than I had realized and Mother and Prudence often spent the entire day shopping in Manchester or Concord. I was never invited, nor did they ever think to surprise me with some new gloves, a scarf, or some other trifling thing.

One day they came back carrying packages; their unusually high spirits seem to suggest there was something other than expensive new dresses and hats afoot.

“Greyson,” Mother said, as she dropped the packages on the table. “I need you to go upstairs to the spare bedroom and move all those boxes up to the attic.” She pulled off her gloves and looked at me. “Make up the bed and put wood in the fireplace.”

“Why?”

“I’ve engaged a housekeeper.”

“A housekeeper?” I asked in astonishment. “Do we need one? Can we afford one?” Prudence looked smug.

“That’s none of your concern,” she replied. “I manage the estate. She will arrive the Monday after next.”

Mother poured a sherry for herself and Prudence as I headed up the stairs. The sound of their laughter set my teeth on edge.

In retrospect, it was apparent we all thought Charity Talmadge would be a dowdy, middle-aged domestic with graying hair pulled back in a tight bun and a no-nonsense attitude. Instead, the last person off the train, carrying a luggage bag and looking uncertainly around, couldn’t have been more different. She was in her mid-twenties with glorious strawberry blonde hair, an admirable figure—from what I could tell—and a breathtakingly beautiful face.

Mother stepped forward. “Miss Talmadge?” she asked curtly. The young woman nodded and smiled. Her eyes radiated kindness and intelligence.

“I’m Mrs. Becket. This is my daughter, Prudence, and my son Greyson.” She looked at me and pointed at the luggage bag. Come get this.

The smugness faded from Prudence’s face and was replaced by a coldness bordering hostility. As Charity shook Mother’s hand and and mine, Prudence hung back, looking at the young woman with a wary, appraising stare.

To say the next few weeks were awkward and unpleasant would be a gross understatement. From sunrise to bedtime, Mother and Prudence watched Charity like a hawk, critiquing her work, peppering her with orders and generally making the young woman’s life miserable. I was gone much of the day on my rounds, but from what I saw in the mornings and evenings left no doubt of the two women’s jealousy of Charity.

One Sunday morning in October, Mother and Prudence were both sick with colds, so I escorted Charity to services. Afterwards, I invited her for lunch at the Red Lion tavern in the heart of the village. It was really the first opportunity I’d had to speak with her privately.

“So, Charity,” I said after we placed our order. “How are you settling in? Are Mother and Prudence keeping you busy?”

She looked at me quickly, not sure how to interpret my remark. When she saw me grinning, she relaxed. “Oh yes,” she said. They certainly are.”

Our conversation was delightful. As we ate, I let her do most of the talking. I couldn’t stop staring at her; her eyes were the deep blue of a cloudless winter sky. The timbre of her voice, her smoothly arching brows, her laugh; I was enchanted. Several times she looked up just in time to see me staring at her and I hurriedly broke off my gaze to concentrate on my mutton. But I also caught her doing the same once or twice.

I think we were both disappointed when we finally reached the house. We paused on the doorstep, beneath what I always thought looked like a lighthouse on the roof.

“Thank you for lunch,” she said. “I enjoyed it.”

“Yes, me as well,” I said. I paused. “Perhaps we could do it again sometime.”

She smiled. “I’d like that.”

As we lingered, our fingertips brushed and we both felt the attraction. Shouting from inside the house broke the spell and sighing, we both entered.

Dr. Wilson was back. Mother had developed a hacking cough that had lasted weeks. She had no appetite, night sweats and her pallor was gray; against her wishes, we called for the doctor, who carefully listened to her breathing with his stethoscope. He took the instrument out of his ears and looked her soberly. The rest of us stood next to the bed.

“I don’t like the sound of your breathing, Clarissa,” he said. “Have you coughed up any blood?”

“Oh, just a little. Now and then. It’s nothing.”

Prudence spoke up. “It’s more than a little, Doctor Wilson,” she said. I’ve seen it.”

Doctor Wilson looked serious. “I need you to get me a sample. Can you do that?” Mother nodded. “I want to rule out consumption.”

In the weeks that followed, Charity’s workload trebled as Prudence insisted that the sheets, towels, clothes and bedding all be washed daily and that Mother was to receive all her meals in her room. The poor girl worked until almost bedtime under Prudence’s sharp tongue, and we had little, if any, time together.

Now and then we might manage a cup of afternoon tea, and our conversation flowed as easily and naturally as the day in the Red Lion. But Prudence seemed to resent our growing friendship and would make up little footling tasks that would send Charity scurrying off as Prudence grimly smiled. Or if Prudence wasn’t around, a hacking cough followed by shouted instructions from upstairs was another interruption that effectively kept us isolated under the same roof.

Dr. Wilson’s initial presumption was correct; Mother did indeed have consumption and her cough had gotten more and more productive with streaks of red soiling the handkerchiefs. His prescribed treatment was more of an order than a suggestion. Mother was to be moved immediately to a sanatorium in Boston.

With Mother gone, there was less work to do and Charity and I had more time to spend together. It became our habit to walk down the frigid February street to the Red Lion several nights a week; the beery hellos from my postal customers, the good food and the warm atmosphere was a welcome relief from the sharp tongue and piercing gaze of my spinster sister.

Now 42, she grew increasingly bitter about Charity and me and our deepening relationship. In our favorite booth, over many dinners and pints, our attraction had grown from friendship to infatuation to love. The first time we kissed was in the tavern, late in the evening, when most of the crowd had left, the fire was low, and the barkeeper was drying glasses and looking pointedly at the clock.

We tried it again in the alcove of the Red Lion and it was even better as the owner shut and locked the door with a cavernous boom. We tried it again walking home, and this was the best of all, slowly, unhurriedly under the glittering stars.

As winter’s grip on New England loosened, we’d slowly walk home along the cobblestone road, holding hands, smelling the first heady scents of spring and stopping frequently to kiss. So this is what it’s like, I thought. No wonder so many people write books about it. I almost felt sorry for Prudence.

Almost.

In the weeks that followed and as the spring flowers gloriously opened, my relationship with Charity also bloomed. We were mad about each other and the word marriage came up several times. It was only the presence of the sharp-eyed Prudence under the same roof that maintained decency and avoided a scandalous situation; but even so, some tongues in town were wagging about the Postmaster and the comely housekeeper and what was going on in the Lighthouse House late at night.

Meanwhile, Prudence’s countenance grew darker and more dangerous with every passing day. Our conversations became strained and the looks she gave Charity could have curdled milk.

Finally one day in early May, the dam broke. After dinner, as Charity and I were washing the dishes—one of the few ways we had to be together—Prudence dropped her bombshell.

“Charity,” she said. Her tone was impossible to describe; spite, hate, jealousy all rolled into a cloyingly sweet poison. “I heard from the sanatorium. Mother is likely never coming home, so we won’t be needing you any more, dear. I’ve made arrangements to pay you through the end of the month. I think you’ll agree that’s very fair.”

She looked at me with glee and hatred; it was the Christmas of the broken train all over again.

I felt panic rising. “Prudence, you can’t do this,” I said. “I won’t let you. Charity and I—“

“Won’t let me?” she mocked. “Won’t LET me? Dear brother, I’m afraid you have no say-so. Mother left me in charge of the estate. This is my house. And I say it’s time for this trampy gold digger to pack her bags.”

She’d had many glasses of sherry. Too many. “In fact, why don’t I help you pack, Charity dear? I’ll still pay you through the end of the month…but I want you gone tomorrow.” She laughed and started climbing the stairs.

“Prudence! I shouted. “Have you gone mad? Let’s just slow down here. Nobody is going to help anybody pack!”

“Greyson,” cried Charity. “What are we going to do? We can’t just let her—“

“I know,” I said grimly. “It’s time that Jezebel got what’s coming to her!” I ran up the stairs with Charity in close pursuit.

Prudence had Charity’s luggage bag open on her bed and she was rifling through her drawers, throwing her few possessions into it with exhilaration. “Oh, the poor lovebirds,” she said pityingly. “Looks like Cupid fell down on the job.” She laughed; it was the most vile thing I’d ever heard.

Charity stood at the top of the stairs, face in her hands, sobbing. “Why are you going this?” she cried. “What did I ever do to you? Why are you so cruel?”

Prudence, despite being intoxicated, moved so quickly I couldn’t react fast enough; she raced past me and slapped Charity so hard in the face that her head whipped to one side. She grabbed her hair and yanked it, slapping, punching, screaming. “Slutty little tramp, I hate you! I wish you’d never come here! I wish you —“

Charity, trying to defend herself, grabbed Prudence by the wrist; but the momentum of Prudence’s frenzied attack carried them backwards. For a second, I thought they had stopped in time; but then in slow motion, both screaming, they fell backwards over the top step, grabbing at empty air and disappearing into the yawning darkness.

A gentle June rain pattered on the mourners’ umbrellas as the Pastor again read the twenty third Psalm. I had a sense of Deja vu; the dismal gray day, the white clapboard church, the pile of dirt, the coffin, the headstones leaning this way and that. I scarcely heard the part about ashes to ashes and the sure and certain hope.

The pastor finished and held his Bible in front of him over his vestments. People shuffled along and took turns placing flowers on the casket: and as they passed, they placed their hands on my wrists and murmured sympathetically. Some dabbed at tears.

As the last of them drifted away, the Sexton nodded and four strong men stepped forward with ropes.

And as we watched—Charity’s arm in a sling—they lowered Prudence gently into the earth.

Note: Because the two NTT pictures I selected depict New England, my story may bear a passing resemblance to Edith Wharton’s novella Ethan Frome. The period, setting, characters, plot, conflict, and resolution are my own. AI art by Meta.

© My little corner of the world 2024

Wonderfully written and hauntingly captivating story. The picture complemented it beautifully.

I’ll be posting something shortly, and I hope you’ll enjoy and appreciate it as well.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Willie! Appreciate you reading and commenting. I’ll be on the lookout for your post 😎

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a great dramatic story, Darryl, fascinating to me.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Tim! I’m glad you enjoyed it! I tried to use archaic language like I’ve read in old books, didn’t want it to com across as pompous, lol. Thanks for reading and commenting 😎

LikeLiked by 2 people

My Dearest Prudence,

Upon the lofty stairway’s height, where shadows weave their shroud, A fierce and gallant struggle soared, amidst the thunder loud. With courage drawn from virtue’s well, we braved the darkened sea, Each step a testament to light, each breath a cry for thee.

In armor forged of kindness pure, we faced the tempest’s might, Our hearts, the beacons in the storm, shone through the perilous night. The clash of wills, the roar of strife, did echo through the air, Yet in the wake of chaos wild, emerged our hope laid bare.

The foes of truth, with venom’s bite, did seek to shroud the day, But in the face of daunting odds, we drove the dark away. With every stroke of justice true, with every shield of care, We vanquished shadows’ cruel embrace, restored the bright and fair.

Oh, Prudence, dear, the dawn now breaks, the darkness swept aside, Upon the stair where valor rose, it’s good that turns the tide. Let this tale of triumph grand forever grace our hearts, For love and light and steadfast souls shall never be apart.

Yours in eternal victory, Charity

Darryl 🙂 Great story and relatable (lol) !!! … Brilliantly written ~ ❤ With the help of AI, I had Charity write a letter !!!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Ah my friend Sirius… the brightest star in the sky… I spoke with Charity and she’s incredibly moved by your poem 😎 Seriously, thanks, that was cool ❤️

I usually let my wife or daughter who’s still at home read my stories before posting. In this case, both howled in protest at the original ending. Poor Charity had died and Prudence was paralyzed from the fall and Greyson was stuck changing her 19th century version of Depends for the rest of their lives. “Whaaaa?” they both said. “”How come CHARITY hasta die? She was so nice…make it Prudence!!” I tried to say life isn’t fair and it was supposed to represent bwah bwah bwah, but they sorta insisted… so ol’ Pru got the boot instead, lol 😂

Thanks as always, my friend, for reading and commenting 😎🙏

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh, you wouldn’t !!!? That would have been horrible (lol) and especially holding back what I really wanted to say 😉 !!! Secretly, Twas hoping Charity got a right hook in and Prudence cushioned her fall … ❤ !!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I thought to myself, ‘I’ll read a paragraph or two for now’. I couldn’t stop scrolling! Lovely story and well written.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, what a compliment! Thank you. I’m glad you enjoyed it, thanks for reading and the kind words. Sorry about the delayed response, I just now saw your comment 😎

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your stories are captivating, Daryl. You kept me involved until the end. I’m glad it was Prudence who died.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks, Mary! Haha, yeahhh… old Prudence … sigh. 😂 Thanks so much for reading and commenting 😎❤️

LikeLiked by 2 people

You have a nice turn of phrase

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Anthony! Appreciate you reading and the kind words 😎👍

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was so amazing, Darryl. I always have to take time to really read and appreciate your stories. You really set the scene for the coming of winter and then the dramatic ending as well 😱 so good 👏 👏 bravo!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you, mi Amiga! When I changed the ending, I had to change the beginning as well… so I made it unclear on who had been dead for 50 years and didn’t make it clear till the very end. Creating characters and making them say or do this or that is so much fun. I’m wondering how much even more fun it would be to write a play (scenes of “Lonely Goatherd” puppet show in “Sound of Music.”) 😂 Thanks as always for reading and commenting! 😎❤️

LikeLiked by 2 people

You’re so welcome! Thanks for explaining your process! I get it, it can be frustrating too changing an entire storyline 🤣 it was quite engaging 🫶

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback https://thebeginningatlast9.com/2024/11/14/no-theme-thursday-11-14-24/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great, good luck and have a nice day, it’s really inspiring

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Noga! Appreciate you reading and commenting, and apparently the procedure went well, too… I’m glad 🙏❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

I absolutely loved the story and the images were integrated perfectly with them. I’m always one for dramatic twists and turns so really enjoyed it.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Awww! Thanks Pooja! Appreciate you reading and our long-distance friendship 😎 Hope your eye is better, sorry for the misunderstanding!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Yes it’s much better thank you! I haven’t even been able to read/reply to the comment but no worries at all 😁

LikeLiked by 3 people

Beautifully written!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks, Dawn! I’m glad you enjoyed it…appreciate you reading and commenting

LikeLiked by 2 people

Another winner, my friend! Outstanding writing! 👏👏👏

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks, Kevin! I hope you have a great TG… thanks for this latest NTT, truly thought provoking 😎👍

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Darryl, and a Happy Thanksgiving to you as well!

I tried to make it a memorable one since we’re putting it to rest for a couple weeks! lol

Glad I got it right 😄

LikeLiked by 2 people

A wonderful story. Bravo.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, AJ! Appreciate you reading and commenting 😎

LikeLiked by 2 people

That was a captivating story, Darryl. I loved that twist. I was very nearly on the edge of my seat, waiting to know whose funeral it was. I’m so glad that it turned out to be Prudence’s. Beautifully written

LikeLiked by 6 people

Thanks, Shweta! Appreciate you reading and commenting 😎

LikeLiked by 2 people

My pleasure, Darryl. Your stories are always very interesting 😊

LikeLiked by 3 people

Beautiful 👏

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you! I’m glad you liked it… thanks for reading and the kind words.

LikeLike

👏 👏

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you! Appreciate you reading and commenting 😎

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow such a beautiful and captivating story

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you! Glad you enjoyed it…thanks for reading and commenting 😎

LikeLike